Charles MICHEL, born on 11th September 1917, graduated of the school of Saint-Cyr, promotion 38/39, September 3, 1939, incorporated into the 98th R.I, (26th DI, 6th CA, IIIrd Army).

Course:

- Made prisoner in Maixe on June 18, 40,

- Arnswalde, Oflag IIB (30 June 40 / 10 November 40)

- Nuremberg Oflag XIIIA (10 November 1940 / 9 September 41)

- Lübben Oflag IIIC (9 September 41 / 26 August 42)

- Münster Oflag VID (27 August 42 / 19 September 44)

- Soest Oflag VIA (20 September 44 / 21 November 44)

- Elsterhorst Oflag IVD (22 November 1944 / 18 February 1945)

- March west 170 KM (18 February '45 / 27 February '45)

- Herrenhaide/ Burgstaedt, makeshift camp in a festival hall (27 February '45 / 14 April '45),

- Liberated by allied troops on 14 April 1945.

To enlarge the photos click on them or on the picto to open them in another window

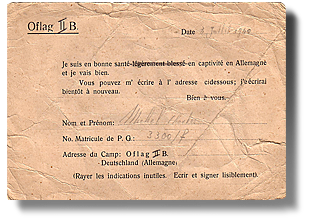

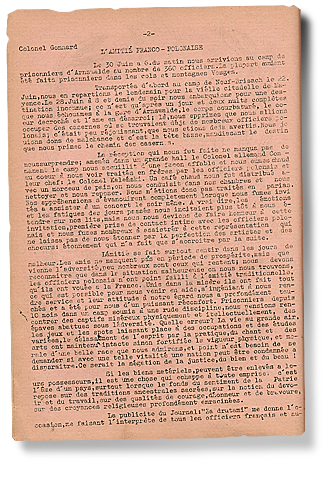

Martine MICHEL's account of the arrival of her father, lieutenant Charles MICHEL at Oflag IIB.

30 June 1940, 6:00 am: The doors of OFLAG IIB close on my father, he is twenty-two years old.

The French general staff was confidently awaiting the German attack which began on the 10th May 1940. Six weeks later, the French army, crushed on all fronts disappeared body and mind.

After surrounding and capturing the armies of the north, the Wehrmacht troops advance along three axes: the southeast, to link up with the Italian forces, the southwest to controle the coastline and the east, to take the armies stationed behind the Maginot Line from the rear. And it was in the east, in Lorraine, that my father was captured along with his comrades in misfortune who were the first French officers taken prisoner on 30 June 1940 in Arnswalde.

The few tens of thousands of Polish prisoners of war, and the million and a half Frenchmen, opened the march that would lead, in the next five years more than five million foreign slaves to Germany.

The "panzerdivisionen" take men from their units to gather, supervise and transport to places of detention columns of hundreds of thousands of unarmed men who march with abandon, guessing that their whole country is collapsing. The Germans in charge, themselves deceived by their superiors, told the French that they would be home within 15 days. This was the first of a long series of lies that the prisoners believed, because until then, the detention of prisoners of war had never been extended beyond the fighting, and, once the armistice was signed, why should they keep people they had no use for? The officers, separated from their men, after making several stages on foot, were regrouped in the "Front STALAG" of the region, such as Sarrebourg or Neuf-Brisach.

A few days later they were put on a train that ran along the Saar valley for a while. The Mainz citadel, DULAG XII, is the end of this transfer, where several hundred prisoner officers of all ranks meet and try to understand the contradictory orders to retreat and attack that have led them to prison.

28 June at 8.30 p.m.: A long column of 354 officers set off in the direction of the station, a painful and humiliating procession in front of the population which had gathered on the pavements.

When they arrived, they piled into cattle cars, squatting against each other, bathed in sweat, towards an unknown destination. The transfer was both physically and mentally appalling, with fear, humiliation, deprivation of food and water, and lack of hygiene, relieving oneself in a corner of the carriage and when the train finally stops in the open country or in the stations, forgetting modesty in collective relief. The relentless heat of June. Those who have kept their compass follow the direction of the train, it goes east, always east! Night falls, they try to sleep, the train rolls on, taking them further and further away from the borders of their country and it is only on the way, when the day comes, when they see the names of the German stations scrolling through the narrow grilled windows of the carriage, that they will admit that they really are prisoners. Hours pass, the train slows down, bypasses Berlin, and finally stops at Tempelhof station, where a ladle of soup is distributed to the lucky ones who have a bowl or a container to drink it from, the others use their helmets or their brodéquin. The train is still heading east with the same noises and bumps, hours go by, night falls, the day rises on a steppe landscape, the towns are far apart, they have no doubt about their destination, it is Poland... 30 June 1940, 6 a.m., the train stops at a small station, the carriage doors open, letting in a breath of air at last. The guards bark at the men to get off 'raus!' and, after passing through the village of Arnswalde they lead a herd of dazed men, still stunned to find themselves there, to the entrance of a light-coloured barracks. The Polish officers, prisoners in this barracks since September 1939, consigned to the blocks, watch the miserable column of French officers arrive. Welcomed in a large hall by the German camp commander and colonel Kalenski, commander of the Polish officers, they could finally eat a piece of bread and drink a hot coffee that comforts them. In the room where he was later taken, did he wonder about the change that captivity would bring to his condition as a man and did he envisage at that moment that his captivity would last five years?